Man, ‘splained: 40-Plus Years of Man Page History

A man page is the most common form of Unix and Linux documentation. Despite the name, they’re not exactly what modern engineers expect from more typical product documentation - and they’re also definitely not tutorials. However, with their own particular format, they’ve become a vital part of regular learning and work for most developers, perhaps the most common “M” in the admonishment to RTM. With something so omnipresent, it’s easy to take it for granted - there’s a utility, so the utility has a man page. Of course.

But the history of man pages is tied inextricably to the history of Unix (in fact, they share a birthday) and is threaded through a certain formative era of computer science. Man pages go back to Bell Labs, back to Jerry Saltzer’s doctoral thesis proposal in 1964, back to decisions that were made without the intention of determining the way certain areas of programming would work for decades. And maybe that’s the biggest lesson of this whole story: never treat a solution as a stopgap or a prototype (particularly if you’re working in Bell Labs in the late 60s or early 70s). Your “This’ll do for today” could become the standard for the generations to follow.

Fortunately, the existence and format of man pages also had that staying power.

So: What’s a man page?

If you’re new to Linux (and the Linux context is where we will be throughout this post), maybe you haven’t encountered a man page yet. The “man” in man page is short for manual, in this case for utilities and programs you access via the Unix or Linux command line.

You can access them in a couple of different ways. The most straightforward one is to type “man” and whatever utility you want explained into the command line. What you get can vary. Some utilities have very specific purposes and are shorter - “man chage” is a good example of a more specific utility with an appropriately concise man page. Some can be lengthy and can function as a class in Linux use and more universal computer science concepts — “man bash” is a notoriously lengthy entry that contains an enormous amount of material.

Man pages can cover a lot of different areas, depending on the needs and scope of what you’re researching. Expect to find libraries and system calls, formatting, formal standards and conventions, and abstract concepts - along with flags, subcommands, positions of arguments, and other things you need to know to use the command.

Some include example commands too. If they don’t, and you’re new to a command or program’s use, I suggest looking up examples from a third party to complement the man page. There are lots out there, and even the less-thoughtful entries are illuminating if you’re just getting your bearings. It’s a lot to ask a newer programmer to extract their particular needed flags and format from a flag salad like this:

Hard for a beginner. Easier with examples.

Where did man pages come from?

Man pages (and, consequently, this blog post) are brought to you by a manager informing his subordinates of what this project would require of them. Let’s go back to Bell Labs, birthplace of both Unix and its man pages (along with many, many other inventions and innovations).

The first Unix release was on November 3, 1971, and the first edition of the Unix Programmer’s Manual shares its birthday.

Dennis Ritchie and Ken Thompson wrote this first version at the insistence of Douglas McIlroy, their manager. (Probably not the very first manager who rode his reports to make sure they did all the paperwork, but very possibly the most influential!) The first version, as you can see, was on paper and collected in a binder, which eventually comprised one volume of the multi-binder Unix OS manual. Today, we access them via the command line or through online repos. This is the modern-day incarnation of something pretty revolutionary - Unix was the first OS to include all of its documentation online in machine-readable form.

Today, the inclusion of a man page or other comprehensive documentation with a new program or utility is considered an essential step in creating and maintaining complete, usable software. Releasing a program without one looks suspicious, immediately giving your intended users cause to wonder where else you skimped on effort.

Tell me about how man pages are put together, though

Like all complex documentation, there are a couple different layers of organization at play here: organization within the manual, and then organization within each individual man page. First, I’ll cover the order of information within each man page, and then I’ll talk about the organization of said pages within the greater manual - and why that matters even though you’re not dealing with a physical binder of information.

Here are all the possible sections of a Linux man page, in their expected order:

Name

Synopsis

Configuration

Description

Options

Exit status

Return value

Errors

Environment

Files

Versions

Attributes

Conforming to

Notes

Bugs

Example

See Also

Generally, no man page will have all of these. Some are typical only to pages within certain sections of the manual. The current man page style guide at man7.org strongly suggests putting whatever you want to tell your eventual users in a form that matches these sections and their order, rather than improvising, reinventing, and needlessly challenging your readers.

My favorites are Examples, Versions, and See Also, as that’s where the authors’ intent and impact tend to come through most clearly, by how they directly suggest you use their work, what they think is most relevant, and how they describe the evolution of their program across versions.

Beyond the sections within the pages, there’s the matter of manual order. When you read a man page or search for one online, you’ll see numbers in parentheses after the commands you’re looking up: sed(1), fdisk(8), exit(3), to name a few. These numbers refer to the physical manual and indicate where in said manual this man page would be, depending on what’s being described. Here’s the current Linux section structure:

General commands

System calls

Library functions, covering in particular the C standard library

Special files

File formats and conventions

Games and screensavers

Miscellanea

System administration commands and daemons

Once you know this, you’ll find the resource you’re looking for faster. If you wanted flags, parameters, and related commands for man, for instance, you’d want its entry in section 1. However, to learn about macro and groff information, you’d want man(7). Or the next section of this post.

The history of man formatting tools, or: Luminaries of computer science, revisited

As I said in the beginning: using something workable and declaring it a prototype or otherwise temporary solution is a risk, particularly during such a formative period of computer science.

The extremely thorough version of the story, complete with correspondence with some of the parties originally involved, can be found at this 2011 research project by Kristaps Dzonsons. If you’re at all inclined to nerd out on this subject, it is well worth spending some time over there. Some of what I’m about to cover is reasonably inferred without the use/availability of primary sources, some is based on primary resources, and all is covered in greater depth at the link.

The story starts with RUNOFF, written by Jerry Saltzer in the MAD computer language in 1964. It was created for the CTSS operating system to format his doctoral thesis proposal for printing. Its next incarnation was called roff, written in PDP-11 assembly. This is the version that was used to format the first three editions of the Unix Programmer’s Manual. It was brought to Bell Labs by Rudd Canaday in 1967 as a prototype for a porting project - but was used for five more years. Despite its relatively long reign as the go-to text formatting utility for early Unix, the PDP-11 assembly source code for roff has been lost. Other original Unix code has been recovered from the original tapes, but roff now exists only as memories and through its impact on the rest of the tools described in this section.

The next incarnation, nroff (or “new roff”) was created in 1972. It was also for Unix, and it created output suitable for simple fixed-width printers and terminal windows. This version, written by Joe Ossanna, was also in PDP-11 assembly and included programmable macros. The next, a year later, was troff (or “typesetter roff”). It was originally in PDP-11 assembly, but Ossanna rewrote it in C a couple of years later. This version worked with the Wang Graphics Systems CAT typesetter and one other output. After Ossanna’s early death, the utility languished until Brian Kernighan picked it up.

Kernighan’s next version of it was called ditroff (for “device-independent roff”), setting the roff family free from its dependence on that CAT typesetter. This version was used by AT&T and derivative Unix systems for many years, so you may find this paper, last updated by Kernighan in 1982, worth a look - it describes his process and decisions around this update, which included fixing font limitations and using dynamic memory.

At this point, it’s the next evolution, groff, that’s present on most Linux and GNU OSes. It was written by James C. Clarke for the GNU Project in C++, based on troff, and originally released as part of SunOS 4.1.4. Since then, there have been tools that work in the same space with names like awf, cawf, and mandoc, but groff is probably what your man pages are formatted with if you’re looking them up with the terminal on a Linux or Mac machine.

This was a lot of detail, but it’s still a higher-level exploration of this history. If you’re intrigued (and it’s worth it to be), dig deeper into that 2011 research project. It’s a fine tour of different forks of different OSes, possible alternate technological realities, and other stabs at making ubiquitous and ubiquitously useful tools for users across several decades.

Man pages, today and tomorrow

These days, there are a few separate (but often overlapping) archives of man pages. The ones you’ll get via your terminal either come with the OS or are added as you install new programs. You can find them at /usr/share/man, where they’re divided into directories using the manual section numbering system I described earlier.

New man pages are typically written by someone on the team that created the utility or program they pertain to. If you inherit the responsibility of maintaining said utility, you also inherit the responsibility of maintaining its man page.

However, you can also find them outside of the terminal - and sometimes, particularly with long man pages, it’s a bit easier to read them in a browser. (It can’t just be me that likes to know the length of what I’m reading before I start.) Michael Kerrisk runs man7.org, a major repo of man pages that also includes great, thorough, opinionated documentation on how to write your own man pages. Other repos, including die.net and kernel.org, are also highly recommended (and appropriately high in search results). These are also great places to look if you’re interested in helping maintain these repos.

But You Want to Write Your Own Man Page

Of course you do!

First thing: get familiar with the formatting. It’s fairly different than any tool I’ve interacted with before, so it takes a context shift. Here’s part of the code for the ls man page on my system, for example:

Tags go at the beginning of the line. If you’re familiar with HTML, this won’t be a complete departure (though there are no closing tags). .TH is the tag for titles, while .SH is for section header. You can format text to be bold or italic with .B or .I, respectively. And .HP, .IP, and .TP are all macros to make those signature indented paragraphs to the right of the command, subcommand, or flag being explained. Want to learn more tags? WTFM: A Gentle Introduction to Man Pages, a presentation by G. Branden Robinson, is one of the more complete resources for formatting tags that I've found.

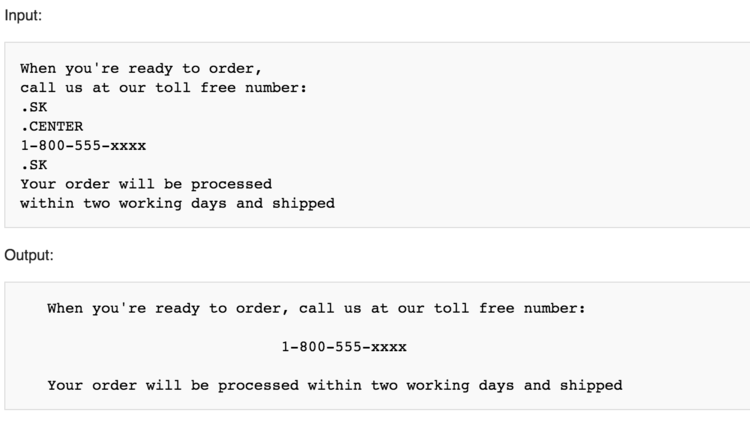

It’s not a sharp evolution from Saltzer’s first version. Here’s a snippet of text made with RUNOFF formatting, for comparison:

Toward a world with more documentation

After studying the strangely integral history of man pages and the tools used to make them, I came away with a few lessons:

Work like it’s permanent. Your stopgap may be someone else’s vital, permanent solution, which may outlive you - or at least your time on the project.

Documentation is important: it lets people use the tools you create to the full extent of their capability and in the way that you intended them to be used. Good managers get that, and good engineers prioritize it.

Include example commands in your man page, if you write one.

Researching utilities now considered standards can yield some great history.

And here are a few tools and resources for you.

Man7.org is a great repo and has the added bonus of being focused on this being a sustainable project, which makes sense as they’ve weathered being passed between several maintainers already.

The kernel.org Linux man pages project is also worthwhile, especially since you can download all the pages as a tarball (in addition to being able to access individual HTML pages).

Julia Evans’ CS-related illustrations can add a wonderful complement to your learning. Some of them cover standard command line utilities, but she covers a wide swath of computer science concepts. There’s probably something for everyone, and it’s all delightful.

BubbleSort Zine also comes at some standard CS subjects from a different perspective, making them a nice counterpoint to documentation that originated at the actual birth of Unix.

And finally, I suggest looking up “[command] examples” whenever you’re looking to learn a new tool. There are a lot of third-party clickbait sites that provide actual useful examples for newbies - usually a good list of ten or twenty of them for some good, varied learning. It’s often what I do immediately after reading the man page itself.

It’s easier to stand on the shoulders of giants if you know where said shoulders are. If you’ve written a man page, thank you. And if you’ve read a man page, take a moment to look back across several decades of work by very wise people and send a little bit of gratitude and acknowledgement back out there into the universe.